|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

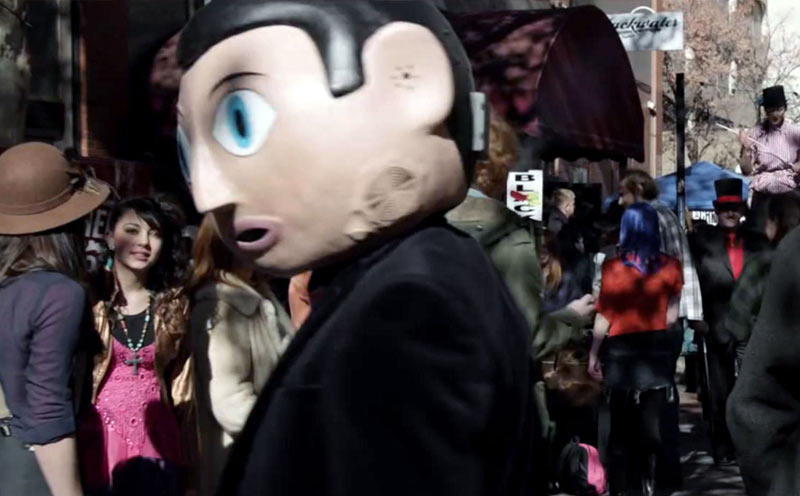

This is not a film about Frank Sidebottom. It is a film about mental illness, the misconceptions of fame and a desire to belong. Lenny Abrahamson’s follow up to What Richard Did is a far cry from Dublin 4 or the rural byways of Garage yet still bares his hallmarks and carves out his name as one of Ireland’s best.

Jon (Domhnall Gleeson) longs to be a songwriter or famous musician and happens upon a band in need of a keyboard player while on the beachfront one evening. He has no idea what lies in store but is more than willing to go along for the ride. The avant-garde electro noise ensemble that is “Soronprfbs” recruit Jon to record keyboards on their upcoming album. Nestled away in a secluded hut in Ireland, we begin to understand the dynamics at work. Don (Scoot McNairy) is a mannequin fancier, Clara (Maggie Gyllenhaal) is on theremin while Alice and Baraque are token Frenchies being French. In the eye of the storm is Frank – a sympathetic, innocent and kind dreamer who is striving for musical perfection, yet unable to handle the pressures it involves.

Gleeson as Jon is everyone who wanted to be in a band growing up, more in love with the idea of fame than any notions of art and the harsh realities. Longing to be unique or creative, he is in awe of Frank and at first dismisses his quirks as endearing and cool as he is unable to see the truth of the situation. The use of social media, especially Twitter, expertly captures the new phenomenon of the digital self. Whereby we show our best attributes and portray an image of ourselves preened and auto analysed to death.

Fassbender is superb in a role that is incredibly difficult. He must evoke compassion, pity, wonder and fear all without any facial expressions. Hidden away from the world beneath a mask he manages to keep our interest until the very end. Gyllenhaal’s character, while important, is a tad cliched yet this is forgiven when the final act arrives.

The screenplay by Jon Ronson and Peter Straughan is unique in providing such believable and three dimensional character arcs for the chief players concerned. No doubt Ronson’s wry sense of humour so prevalent in his journalism is the source of the film’s funniest segments. It is surprising to see a run time of ninety five minutes with the piece incorporating so much and never dragging.

Frank is definitely a big departure for Abrahamson and it will be interesting to see how it plays as, even with its relentless PR campaign, this is not a mainstream film by any stretch of the imagination. It is when the band is recording the album that a familiar Lenny can be seen with scenic shots and light gently flooding the cabin. Without question the final twenty minutes cement the piece as a film of note with a worthy message making it a departure from the norm by slowly building to an earnest conclusion.

There are numerous talking points or angles to view the film from but ultimately Frank is a sweet, funny and poignant look at the realities of the tortured artist.