|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

For The Social Network, the movie about Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg, screenwriter Aaron Sorkin created a fast-talking, arrogant, emotionally illiterate genius-innovator obsessed with boardroom betrayal. For Steve Jobs, on the other hand, he's created a fast-talking, arrogant, emotionally illiterate genius-innovator obsessed with boardroom betrayal. The tropes are familiar, but this is still another very exhilarating and exasperating two-hour guitar solo of a movie from Sorkin, an alpha male display of cerebral confrontation and conceit featuring a male diva to whom respect must be paid and with whom arguments are humiliatingly lost. Sorkin's writing is a bipolar rush. For each of his films there must surely be another, unreleased one with all the same characters, who stay in bed all day and stare at the wall.

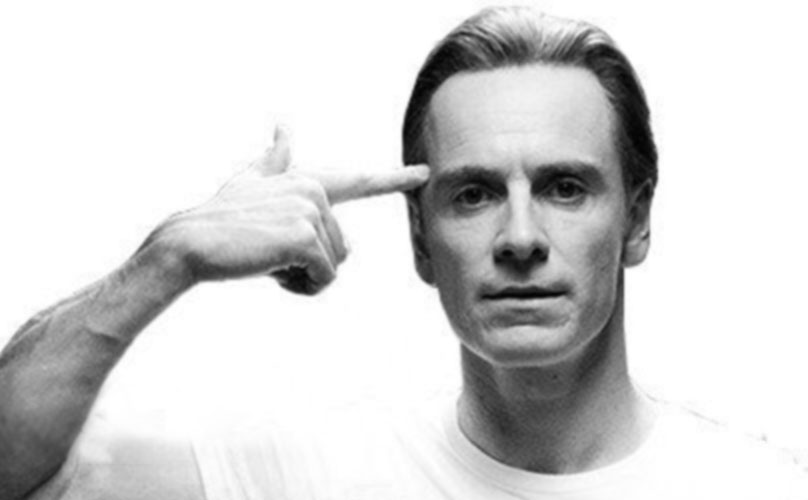

This film about the great Apple designer Jobs, played by Michael Fassbender, is an intimate and theatrically ingenious piece, adapted from the authorised biography by Walter Isaacson. It focuses on three private crises: Jobs's backstage meltdowns before the product launches of his Apple Mac in 1984, his ill-fated NeXT computer in 1988, and the iMac in 1998, by which time he has fully developed his sartorial style of rimless glasses and black polo-neck tucked Seinfeldishly into laundered Levi's. The extraordinary moment at the beginning showing an eccentric approach to foot-washing is neither remarked on nor repeated.

Each event looks like the prelude to a TED talk in hell. Daniel Pemberton's musical score jitters each scene to a nerve-jangling climax, and there is an amusing touch of the Downfall spoof about each of Jobs's trio of tempests. Maybe one day Sorkin will write about Hitler's private behaviour before the invasion of Poland in 1939, France in 1940 and the Soviet Union in 1941. Or perhaps three broodingly intellectual scenes for Col Kurtz before three different cow-slaughtering jungle ceremonies in 1966, 1967 and 1968.

There are the classic Sorkinian prose arias, walk-and-talk riffs and high-impact dialogue of the sort really only David Mamet can match. And of course impossibly smart comebacks. "God sent his only son on a suicide mission," says Jobs, “but we like him anyway because he made trees."

This indoor firework display is smoothly realised by director Danny Boyle who balances and coordinates Michael Fassbender's star workload and screentime with that of his supporting cast: long-suffering marketing executive and confidante Joanna Hoffman (Kate Winslet), tricked out in nerdy hair and glasses, designer Andy Hertzfeld (Michael Stuhlbarg), CEO and quasi-dad John Sculley (Jeff Daniels) and former Apple compadre; and quasi-brother Steve Wozniak (Seth Rogen), who feels horribly abandoned and let down. It is perhaps a drawback of this film, or of Jobs’s own monomaniacally driven existence, that the characters who have the least presence are those who have only a non-professional or purely human connection with Jobs: the troubled mother of his child, Chrisann (Katherine Waterston) and his neglected daughter Lisa, finally played in adult life by Perla Haney-Jardine.

Fassbender gives an entirely fluent and commanding performance, although oddly it was poor old Ashton Kutcher in the unloved 2013 biopic Jobs who resembled the great man more, with a more saturnine and quizzical face. Fassbender's performance is harder, fiercer and blanker, understandably as a result of showing him at three of the most unrelaxed times of his life.

This Steve Jobs is a bully and a blowhard who runs on the rocket fuel of pure male self-pity. He is obsessed with betrayal, that is, other people’s betrayal of him – like the colleague who talked about his private life to Time magazine, and Sculley, who he feels ousted him from Apple in the 1980s. But he has a tough time understanding that he has betrayed his daughter by not acknowledging her, and has betrayed his old buddy Steve Wozniak by refusing to acknowledge the work done by Wozniak's team on the earlier product, the now uncool and obsolete Apple II. With icy ruthlessness, he is concerned only with the future, and maybe the film is even hinting at the import of Wozniak's nickname "Woz" – a hint of "was". Jobs is concerned only with what will be.

The final scenes are, arguably, contrived and emollient. Yet we are still left with a drama that is genuinely concerned with thinking and ideas relevant to the way we live now. If Boyle and Sorkin want to go on to make a movie about a glamorous innovative genius who was not a man, I suggest Hedy Lamarr, the Hollywood star who patented communication technology that made mobile phones possible.