|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

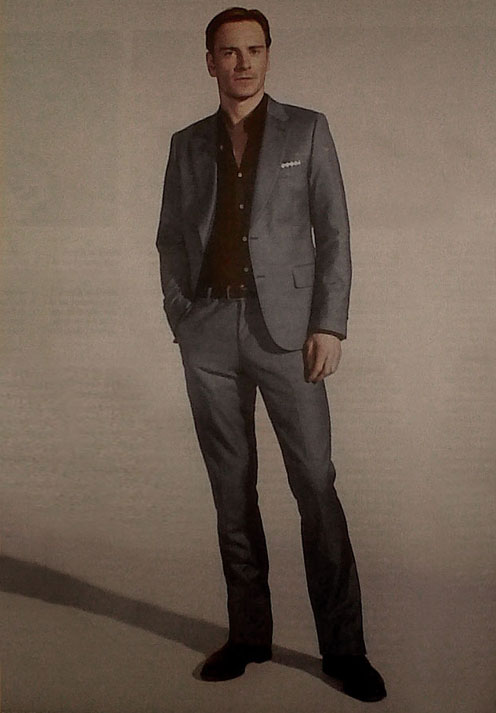

When Michael Fassbender enters the room wearing a raffish trilby, my thespian-o-meter tilts to max. Actors wear hats to go around unrecognised, although since headgear always draws the eye, it seems a covert look-at-me ruse. But later when, reluctantly, at my request Fassbender removes it, I realise I've misjudged him utterly. He is trying to conceal the most theatrical thing about him, an uneven, garish blond dye job for the role he is currently filming, Ridley Scott's Prometheus.

It's like an early David Beckham, I say. "Jesus!" he exclaims. "That's not bad. I thought I looked like a ten-quid rentboy."

Even after a long day of X-Men press interrogation, he is open and unspoilt, grateful for the gods' present favour but – like all who had a long haul to success – aware it may not last.

"I had a lot of lean years where I wasn't working," he says. "Sometimes I think you are holding on to something so tight you come into a room and reek of desperation. It's a terrible Catch-22: if you work you get the confidence, but in order to work you have to show them something you've done. I made a balls of so many auditions, lost so many jobs."

If acting didn't work out, his Plan B was to open a bar. It was no bottom-of-the-whisky-glass whim. He was raised in the restaurant trade: his father a chef, his mother front of house. They ran a restaurant called West End House in Killarney, County Kerry, until they retired recently. Michael worked in the kitchen, helped unload deliveries. He saw his parents struggle in their first few years, the toll a small business takes on a marriage when money is hard-won. "I'd ask for trainers or fashionable clothes and be told we couldn't afford them. It teaches you a lot. It surprises me the people of my age who turn around and say, 'It's not fair!' I learnt that very young."

It was not a bad preparation: "You always have to be smiling and happy when you're front of house, no matter what is going on in the kitchen or in your own life."

Michael was a dreamy child who, since most of the neighbourhood kids, like his sister, were older than him, spent much time alone. He would pretend to be the Six Million Dollar Man or the Fall Guy: "I was flying a spaceship, being Superman and climbing trees. I was always living in little pockets of fantasy, but I never thought of acting until I was 17." He was a teenager when his parents took on West End House, which was opposite his school, so while they lived a few miles away, Michael was allowed to stay in the restaurant. "I didn't take the p***. I respected the freedom they gave me."

He is still very close to his father, Josef, mother, Adele, and his sister Catherine, a neuropsychologist who researches ADHD in children. His baby talk was German and his mother, who learnt the language, insisted they talk it at table in Ireland, which embarrassed him at the time. Summers were spent with German relatives, so he speaks the language (rustily) still, well enough to appear in a film sometime.

There is a driven, organised Teutonic side to him that he attributes to his father. "If I came home with 85 per cent in a test, he'd always ask what happened to the other 15 per cent. It was awful at the time. I was like, 'I can never please this guy.' But it is useful now."

His mother shared with him her passion for Seventies films, the movies of the great method performers Pacino, De Niro, John Cazale and Christopher Walken. He started reading about the Lee Strasberg school method, directed a group of friends in a production of Reservoir Dogs.

In his career there are two films that drew on method levels of physical dedication. The first was 300, in which he had to bulk up to play a Spartan warrior: working out for ten weeks, four hours a day, five days a week, before even going in front of camera. "But that's fun. You get the best people training you and you get paid to look good and feel strong."

The second was in Hunger. At the film's centre is a powerful dialogue with a priest, in which Sands attempts to reconcile his political action with Catholic theology: is hunger strike martyrdom or deadly sin?

After this central scene was shot, the production was closed down for ten weeks while he was loosing the weight.

During his fast, he rented a house in Venice Beach, Los Angeles, where he spent his days walking and doing yoga.

He ate nuts and berries, plus endless cans of sardines: "I thought they would be good for me; they have calcium."

He was surprised to find he had so much energy he could hardly sleep. "It's pretty frightening. I started to understand how mentally all-encompassing it becomes and what it must be like for people with eating disorders."

"I was kind of monk-like. It was like the 40 days and 40 nights alone in the desert. In a practical way, if you have friends around they will say, 'Let's eat this packet of crisps while we watch this movie.' It weakens you. I thought, 'I will stay on my path.'"

Later he will return to LA, no longer a naif, but with the power and maturity to get what he wanted. "I was not at the industry's mercy any more." But he stayed only as long as he had to, finds that LA lacks a sense of humour about itself and gets bored by the monomania of a one-industry town. "I'm afraid of what I could become if I lived in LA for too long."

Clearly he is self-reliant, doesn't mind the solitary preparation, the dislocation of being away on set, living in hotel rooms for the past few years. "I think that is my trump card in this industry," he says, "That when I put my mind to something, I go for it uncompromisingly."

So what did you learn making X-Men? He grins, "I learnt how to bend metal. It took a while."

As a young Magneto he enters a rich franchise with all its likely intrusions. But he cites the example of Viggo Mortensen, who despite starring in The Lord of the Rings trilogy, keeps a low-key life.

Besides, Fassbender avoids industry parties, is suspicious of the seduction of stardom, and finds a creativity in London and New York he never found in LA. His niggling worry is of losing connection with reality: "Suddenly you are in big films and everyone gives you free s***. You can get too enticed by it so you don't want to lose those things. And you think, why didn't you give me that free suit ten years ago when I couldn't afford to get a bus?"

Asking how it feels with such a haphazard life, away for weeks or rising at 4am: "At the moment my job is the most important thing for me. I want to give it everything I can."

"I think it is important not to lose the idea that we’re all reliant on each other and interconnected.

What I am trying to say is that when you get on the Tube, if you ask the person who sells you the ticket how they are and they're like, 'I'm good, how's your day?', that exchange feeds you and feeds them. You get so much out of that in terms of feeling there is a purpose. Rather than always thinking how I can achieve the best for me."