|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Actor Michael Fassbender is the latest in a long lineage of irresistible Irish heart-throbs/

Jo Ellison is enthralled. Portraits by Boo George

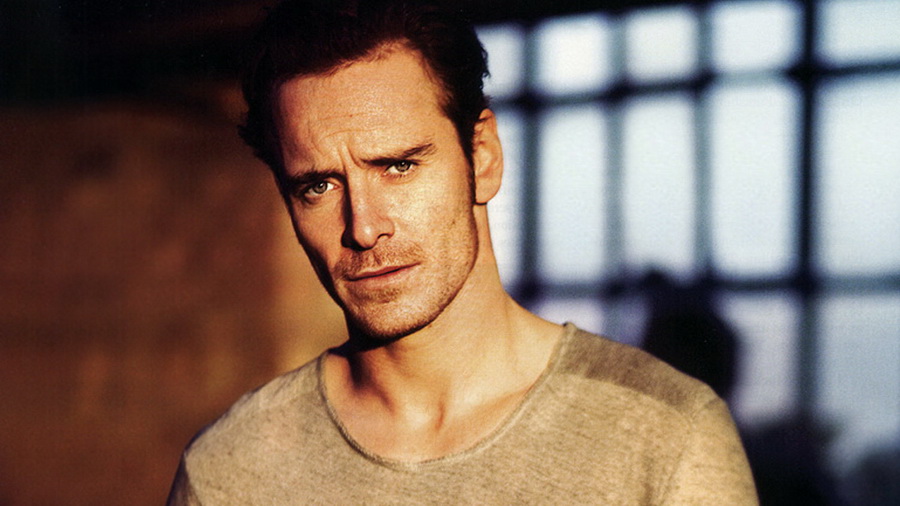

Michael Fassbender is a strolling down Broadway Market, by London Fields. It's a perfect day in late autumn" a chill wind blows, the sun is bouncing of the tarmacadam, and the leaves are a pantone wheel browns. He's wearing Evisu jeans, a navy tee, Adidas trainers and nut-colored biker jacket. He wears them well. Shoulders back, with an easy gait and a Marlboro on the go, the 33-year-old actor looks as cocksure and carefree as one of the local barrow boys.

I am scuttling along two steps behind. I do not look carefree; I am dry-mouthed, over-exited, and completely neurotic. I've done, undone and done my hair three times. I've tortured my eye make-up to the point where it looks painfully conjunctival. I dressed up, but feel all wrong. I am first-date nervous.

Fassbender enters The Dove, a small pub towards the south end of the market, and is already scanning the bar when I introduce myself. We have met in the past-across table, at an awards ceremony, about two years ago but I doubt, somehow, that I burnt as singular an impression on him as he did on me. He focuses his steely blue eyes on mine and grins.

"Hellooo, Jo," he exclaims in a powerfully gentle Irish vernacular while pulling me into the type of embrace usually saved for long-lost relatives or air-crash survivors. "It's great to see you." A long-held maxim counsels journalists never to meet their idols. I have always assumed this is because such encounters will be bathetically disappointing. I now realize they simply leave you at risk of complete coronary failure. Thankfully, Fassbender hasn't heard my heart thunder-clapping, and is busy ordering us drinks and voicing his woes about the theft of his motorbike, which was stolen from outside a restaurant earlier in the week and which isn't insured because: "I didn't have a secondary lock on it. And when I asked the police if I could see the CCTV footage from one of the four cameras trained on to that particular spot they said I had to get permission from everybody else captured on the CCTV footage, which is impossible." He lights another cigarette and assist me to do the same. He has a strong, manly jaw line and surprisingly delicate hands; maybe pianists' fingers are a Teutonic trait. You can be sure of one thing: his talent for talking is pure Celt.

"There's this notion that the cameras are there to protect the citizen, but actually they're only there to facilitate the state in the prosecution of the citizen," he continues. A dog wanders past. Fassbender indulges it in a minute of friendly petting before suddenly standing up. "I'm done with this," he announces of a half-finished orange juice and lemonade. "Shall we wander up the road and see what we fancy for lunch?" His hair is backlit in a sandy halo as he sets off up the street. I follow his silhouette as devotedly as the aforementioned dog. But who, you ask, is Michael Fassbender? Indeed. Thus far, the oeuvres that have defined his career have consisted either of highly cerebral, highly acclaimed, highly difficult arthouse films like Hunger ( for which he starved himself to 50 kilos to play political prisoner Bobby Sands, Angel and Fish Tank, or highly gory, highly popularist and often hilarious efforts like Inglourious Basterds, Eden Lake, or Centurion in which he ran around the New Forest dressed in little other than a Roman loin cloth).

In fact, a great many of his roles have required the removal of his clothing for sustained periods of time. But even though he packs as perfect a pectoral as any other young Adonis, it's his acting skills that dazzle.

On-screen, Fassbender is charismatic, brilliantly generous and utterly compelling; you can't wrest your eyes from face. But don't take my word for it. Ask a film-maker: "He's like a musician," says Steve McQueen, who directed him in the Bafta-winning Hunger and with whom he is now working on a new project. "He can insinuate something in a performance in a way that is unrecognizable, but also familiar. That's what makes him so mesmerizing. He's very hypnotic, but there's a bit of roughness there. It's very human. You know it smells."

"I've been lucky enough to work with some of the best actors in the world," adds director Matthew Vaughn, listing Robert de Niro, Brad Pitt and Nicolas Cage among them. "And I can guarantee that Michael Fassbender is about to join them in rank and stature."

This year Fassbender will star in no fewer then four films: he plays Jung opposite Viggo Mortensen's Freud and Keira Knightley in David Cronenberg's psychoanalytical drama A Dangerous Method; he co-stars in Steven Soderbergh's Dublin crime caper Haywire (with Ewan McGregor); corset lovers will swoon over his performance as Mr. Rochester, opposite Mia Wasikowska's Jane Eyre, in a sinister re-telling of the Bronte Classic, directed by Cary Fukunaga. And right now, he's donning the latex as Ian McKellen's former alter-ego Magneto in Vaughn's re-booted X-Men: First Class, filming at Pine wood, and due out this summer. The film's nightmarishly complicated production has seen this meeting rescheduled numerously, and meant he missed out on a plum role in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy. Suffice to say, having seemingly come from close to overexposure.

In Fassbender is comfortable with his apparent overnight fame, it's because it's been a long, long time in the making. Having dropped out of drama college as a 20-year-old, he spent the best part of decade struggling to get the small breaks before landing his golden ticket. "The wildnerness years..." he mulls over a chicken sandwich in a local cafe whose coffee machine specializes in an appalling screech that near-obliterates cogent conversation, but whose geography virtually necessitates my sitting in Fassbender's lap - which is fine by me. "Well... I was working. I mean, God, there are people in the wilderness who are really in the wilderness," he explains. But the actor's life was "very sporadic: you know a guest spot in Holby City. Six episodes on something here or there. Working behind a bar. A lot of thinking should I go home. And I made a balls of soooo many auditions."

This is not false modesty. McQueen barely remembers Fassbender's first audition to play the hunger-striker Bobby Sands. "He didn't make a deep impression on me." It was only on meeting him for a second time that he saw his true potential. "He's a beautiful person. It's difficult sometimes, when you're introducing yourself to someone. Your first impression can always be wrong. And once the barriers were down I thought, this guy's amazing."

Unquestionably, his harrowing performance as the IRA prisoner changed very everything. The film went on to win 33 international awards, including the Camera d'Or at Cannes, and established Fassbender as a leading man. "It was everything," he says of the film. "The film industry was going to go through a breakdown and there were less jobs for less people Hunger changed my life..."

But even if his fortunes have changed, Fassbender is under no Illusions about his sudden currency. "Talent is a very small per cent of success there are massively talented people out there who will never be seen on screen or on stage. People always go on about talent, but you've got to have the chance; meet the person who will work with you, and with the script that just suits you. Timing is massive."

Neither does he allude to any mystery regarding his methodology. "I read an interview with Roy Keane," he says, conjuring Ireland's colourfully controversial former football captain. "He said: 'I may not be able to dribble like Giggs, or pass the ball like Beckham. So I just have to work harder than anybody else.' That might be him giving a humble description of himself, but it's a pretty good work ethic to apply to everything," says Fassbender, getting up to grab an outside table in the sunshine. "I bring a very pragmatic, practical process to acting," he continues. "The boring stuff. It's about graft. It's as simple as that. When I get a script I'll just read it, read it 200 times over and over, I'm sick of it. And then you can have fun with it."

He many argue that his process is boring and prosaic, but Mia Wasikowska paints a different picture. "To work with someone like Michael is to have and ally and friend," she says. "from the beginning I felt fiercely supported by him. He brings with him a worldliness that informs his performances, a depth of emotion that is both raw and beautiful, and an inflectionally cheeky energy that would lift the whole crew." She talks also of his "honest curiosity", a trait writ large through all his conversations, and his sense of humor. "I had the most incredible fun working with him." The feeling's mutual: "She's phenomenal," he says the 21-year-old actress. "She taught me so much."

Fun is a big factor in Fassbender's life. I can only assume it was what directed his decision to take part in Centurion a sword-and-sandal slashathon set in ancient England or 300. Fassbender laughs. He blames the cause of this particular professional peccadillo on Dominic West an actor alongside whom Fassbender has starred three times. "I was working with Dominic [in South Africa]. Both of us love riding horses, and we used to go off on these trails around the vineyards; it was amazing. I said to my agent after that: 'I'll do anything with horses!" Besides: "It's fun doing the things that you do when you're 10, to do something that's a bit more physically involved, and flush out your brain."

Just as he loves horses, so, too, does he love motorbikes. And racing cars. And go-karting. "It's a horrible weakness a materialistic failing of mine," he admits. "I used to go to the cinema all the time. Now I go go-karting, and test-drive motorbikes. I love cars. I would love to have a collection. I'd love a 1956 Porsche 550 Spider. To me that's like a Van Gogh." I wonder whether I could share my life with a man who might liken Porsche to a Van Gogh, and decide I probably could. But it seems not everyone is so understanding. "Whenever you're taking to the female population about a Ferrari, they're like: 'that's just like the extension of a dick.' And you're like: 'no, it's a beautiful piece of art."

We pay up. Or rather Fassbender pays up. He has a driver waiting to take him into town. Can he offer me a lift? We pile into the car to make our way through hellish traffic onto town. Meanwhile, Fassbender chatters on, debating the merits of the new Bugatti or BMW motorbike he wants to test-drive. Slowly, the conversation turns to film. Have you seen The Social Network? I loved it. Fassbender found it boring. He's a difficult audience. In too many films "I know what's going to happen after the first 10 minutes." The Social Network was evidently one of those. We talk about hundreds of actors currently crowding the lot at Pinewood, where Captain America, X-Men and Pirates of the Caribbean are in production. We finally arrive on Bond Street, and I take my cue to leave. Fassbender leaps out of the car and gives me another of those hugs. He grins over the exhaust fumes and disappears.